SOLID is another staple of object-oriented programming and is found in some form in pretty much all modern code stacks. As such, it is a really strong concept to learn, apply with and be questioned on as it is inevitably an interviewers favourite question set.

What is SOLID?

SOLID is an acronym so it’s actually surprisingly easy to remember. I’ll spell them out and then go through each one, in turn, to explain it a bit further. This is a high-level view of the SOLID principles and doesn’t go too far into the detail. You can (and people have) written entire books on these and if you want to learn more about them I would highly recommend you do so! Robert C Martin is credited with SOLID, so check out his work especially.

- S – Single-responsibility

- O – Open-closed

- L – Liskov substation

- I – Interface segregation

- D – Dependency Inversion

Single-responsibility Principle

The single responsibility principle is fairly self-explaining. The idea behind it is that each class should only be responsible for a single thing. Take an example class of ManageBasket, this class can have methods for adding, updating and deleting items in the basket and comply with a single responsibility. The purchase of the items, however, should be managed by its own class as the responsibility is different (manage versus purchase).

What I love about this meme is how clearly this communicates this concept. The Swiss army knife can do everything, but just like a class, the more responsibility you give it, the more confusing it becomes.

Open-closed Principle

Open closed principle states that once created, a class should be open for extension and closed for modification. This is actually less complex than it sounds as basically once you have created a class you shouldn’t modify it again. This is because once you have created a class and have systems using it, modifying it directly risks strongly some form of break happening with inconsistent behaviour between the two versions of the said class.

If you need to alter the behaviour, (and modification is closed) you can extend the model (extension is open to you) by inheriting it and adding your new methods/functions to this class instead. This gives you the full functionality of the original (and unmodified it will not break any existing uses) whilst allowing you to develop new features in a safe way.

Liskov Substitution Principle

This one got me all confused, so hopefully, I can clear it up for you and save you that confusion.

In short, this principle states that a derived class should be substitutable for its base class and work as expected without modification.

What this means in practice, is that if you have a class for Person and a derived class for Student then the method called ‘Get Age’ in Person should return correctly regardless of whether you call Person or Student. If the Student overrides the functionality of Show Age to return a string instead of an int, then it would fail the principle as the return behaviour is inconsistent.

The meme is a good reminder of this principle, as it makes light of the scenario and hopefully a bit easier to remember!

Interface Segregation Principle

The idea behind this one is that “no client should be forced to depend on methods it does not use”. What this actually means is that a class should be correctly abstracted so only have the methods it needs (think Single Responsibility). It also allows for larger classes (more common in historical work) where clients can interface with only the methods they need and not be exposed to those they don’t.

The easiest way to explain this is the meme – a client needs to use the ‘charge device’ class. They want to plug in a USB. They do not need, Fire Wires, VGAs or HDMIs. Interface Separation Principle allows for a large ‘Charge Device’ class with interfaces for ‘iUSB’ etc to only implement the methods they need.

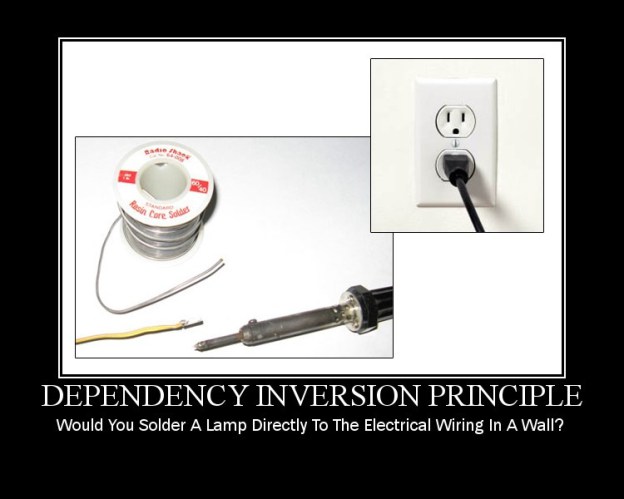

Dependency Inversion Principle

Dependency Inversion is a design principle to limit the effect of changes to low-level classes in your projects.

Think of a base class like ‘make call’. This class worked great 50 years ago when calls were only made in one way, but now we can make wi-fi calls, skype, whatsapp and more. To add these into our bad example would require modifying the base class to enable support for other methods and means that every time we add or edit one of these we would need to test all other versions because they derive from the same class.

Dependency inversion states that classes should depend on abstractions. So in this case, we could define an interface for the call and them implement methods for ‘Landline’, ‘Skype’ etc.

Image Credits

I’ve used memes from a great blog by Derick Bailey that went through the SOLID principles. The memes don’t seem to load on that page anymore, so hopefully collecting them here will bring a smile to someone’s face and not just mine!

1 Comment